|

| Frank Lloyd Wright |

|

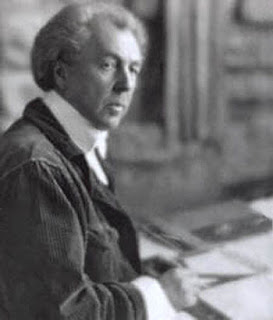

| Darwin D. Martin |

On January 2 this year I posted a blog that included this statement:

"I had a client once -- Darwin D. Martin -- he made the Larkin Company what it was when it was something; behind him on the table in the dining room was a big dictionary. After I had built the house, I was building other buildings and I used to dine there often, and this thing would come up and Mr. Martin would go over to that dictionary two or three times during a meal -- finding out. And he was a self-educated man; never went to college, didn't have much schooling: he was "the boy from Missouri [Valley]" that Elbert Hubbard wrote a piece about once. But his tireless, ceaseless curiosity concerning everything! And he became a remarkably educated man. He was a Christian Scientist, so far a religion went -- which was kind of a bar across his path -- but still he got somewhere; he was a religious man, and he was the man who had me do the Larkin building. So, the dictionary act is a thing I have inherited; I don't do it often enough. Every morning, we should have this dictionary behind here, because we are going to need it..."

I was mystified and wrote, Tantalizing ! Who is this man? What more does he have to say in the rest of the manuscript? and went on to speculate that it could have been Paul Mueller the supervisor of construction of the Larkin Building. But several readers replied that they thought it had to be Wright himself and they were correct. A copy of the manuscript

fragment was sent to me in 2005 by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, the director of the Archives of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation to which the text should be credited except that in the interim the archives have been transferred to the Avery Architecture and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University where I suspect the rest of the manuscript can be found. It is indeed Wright and it indicates that several years after Martin's death Wright remembered, admired, and learned from the businessman he called his "best friend."

(Thanks goes to Matt Guerin)